MARY ERSKINE

A Franconia Story,

BY THE AUTHOR OF THE ROLLO BOOKS.

NEW YORK: HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS. FRANKLIN SQUARE.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1850, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Clerk's Office for the Southern District of New York.

PREFACE.

The development of the moral sentiments in the human heart, in earlylife,—and every thing in fact which relates to the formation ofcharacter,—is determined in a far greater degree by sympathy, andby the influence of example, than by formal precepts and didacticinstruction. If a boy hears his father speaking kindly to a robin inthe spring,—welcoming its coming and offering it food,—there arisesat once in his own mind, a feeling of kindness toward the bird,and toward all the animal creation, which is produced by a sort ofsympathetic action, a power somewhat similar to what in physicalphilosophy is called induction. On the other hand, if thefather, instead of feeding the bird, goes eagerly for a gun, in orderthat he may shoot it, the boy will sympathize in that desire, andgrowing up under such an influence, there will be gradually formedwithin him, through the mysterious tendency of the youthful heart tovibrate in unison with hearts that are near, a disposition to kill anddestroy all helpless beings that come within his power. There is noneed of any formal instruction in either case. Of a thousand childrenbrought up under the former of the above-described influences, nearlyevery one, when he sees a bird, will wish to go and get crumbs to feedit, while in the latter case, nearly every one will just as certainlylook for a stone. Thus the growing up in the right atmosphere, ratherthan the receiving of the right instruction, is the condition whichit is most important to secure, in plans for forming the characters ofchildren.

It is in accordance with this philosophy that these stories, thoughwritten mainly with a view to their moral influence on the hearts anddispositions of the readers, contain very little formal exhortationand instruction. They present quiet and peaceful pictures of happydomestic life, portraying generally such conduct, and expressing suchsentiments and feelings, as it is desirable to exhibit and express inthe presence of children.

The books, however, will be found, perhaps, after all, to be usefulmainly in entertaining and amusing the youthful readers who may perusethem, as the writing of them has been the amusement and recreation ofthe author in the intervals of more serious pursuits.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

- I.—JEMMY

- II.—THE BRIDE

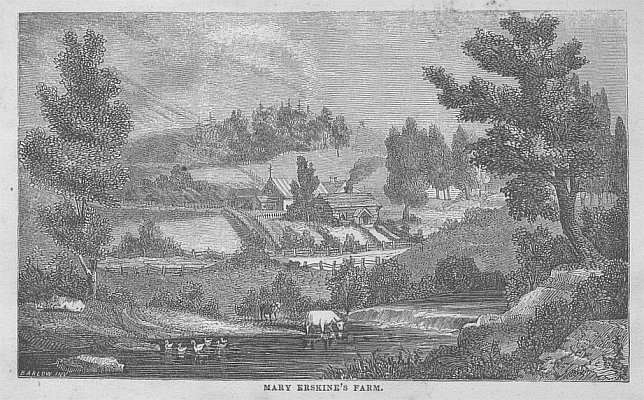

- III.—MARY ERSKINE'S VISITORS

- IV.—CALAMITY

- V.—CONSULTATIONS

- VI.—MARY BELL IN THE WOODS

- VII.—HOUSE-KEEPING

- VIII.—THE SCHOOL

- IX.—GOOD MANAGEMENT

- X.—THE VISIT TO MARY ERSKINE'S