Message From Mars

By CLIFFORD D. SIMAK

Fifty-five pioneers had died on the "bridge of

bones" that spanned the Void to the rusty plains

of Mars. Now the fifty-sixth stood on the red planet,

his only ship a total wreck—and knew that Earth

was doomed unless he could send a warning within hours.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

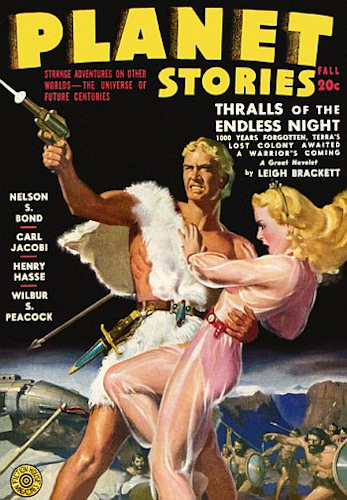

Planet Stories Fall 1943.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"You're crazy, man," snapped Steven Alexander, "you can't take off forMars alone!"

Scott Nixon thumped the desk in sudden irritation.

"Why not?" he shouted. "One man can run a rocket. Jack Riley's sick andthere are no other pilots here. The rocket blasts in fifteen minutesand we can't wait. This is the last chance. The only chance we'll havefor months."

Jerry Palmer, sitting in front of the massive radio, reached for abottle of Scotch and slopped a drink into the tumbler at his elbow.

"Hell, Doc," he said, "let him go. It won't make any difference. Hewon't reach Mars. He's just going out in space to die like all the restof them."

Alexander snapped savagely at him. "You don't know what you're saying.You drink too much."

"Forget it, Doc," said Scott. "He's telling the truth. I won't get toMars, of course. You know what they're saying down in the base camp,don't you? About the bridge of bones. Walking to Mars over a bridge ofbones."

The old man stared at him. "You have lost faith? You don't think you'llgo to Mars?"

Scott shook his head. "I haven't lost my faith. Someone will getthere ... sometime. But it's too soon yet. Look at that tablet, willyou!"

He waved his hand at a bronze plate set into the wall.

"The roll of honor," said Scott, bitterly. "Look at the names. You'llhave to buy another soon. There won't be room enough."

One Nixon already was on that scroll of bronze. Hugh Nixon,fifty-fourth from the top. And under that the name of Harry Decker,the man who had gone out with him.

The radio blurted suddenly at them, jabbering, squealing, howling inanguish.

Scott stiffened, ears tensed as the code sputtered across millions ofmiles. But it was the same old routine. The same old message, repeatedover and over again ... the same old warning hurled out from the ruddyplanet.

"No. No. No come. Danger."

Scott turned toward the window, started up into the sky at the crimsoneye of Mars.

What was the use of keeping hope alive? Hope that Hugh might havereached Mars, that someday the Martian code would bring some word ofhim.

Hugh had died ... like all the rest of them. Like those whose nameswere graven in the bronze there on the wall. The maw of space hadswallowed him. He had flown into the face of silence and the silencewas unbroken.

The door of the office creaked open, letting in a gust of chilly air.Jimmy Baldwin shut the door behind him and looked at them vacantly.

"Nice night to go to Mars," he said.

"You shouldn't be up here, Jimmy," said Alexander gently. "You shouldbe down at the base, tending to your flowers."

"There're lots of flowers on Mars," said Jimmy. "Maybe someday I'll goto Mars and see."

"Wait until somebody else goes first," said Palmer bitterly.

Jimmy turned about, hesitantly, like a man who had a purpose but hadforgotten what it was. He moved slowly toward the door and opened it.

"I got to go," he said.

The door closed heavily but the chill did not vani