THREE GOOD GIANTS

WHOSE FAMOUS DEEDS ARE RECORDED IN THEANCIENT CHRONICLES

OF

FRANÇOIS RABELAIS

COMPILED FROM THE FRENCH

BY

JOHN DIMITRY, A.M.

Illustrated by Gustave Doré and A. Robida

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

Copyright, 1887

BY TICKNOR AND COMPANY

All rights reserved

AN EXPLANATION BY WAY OF PREFACE.

I freely admit what all theworld knows about FrançoisRabelais.

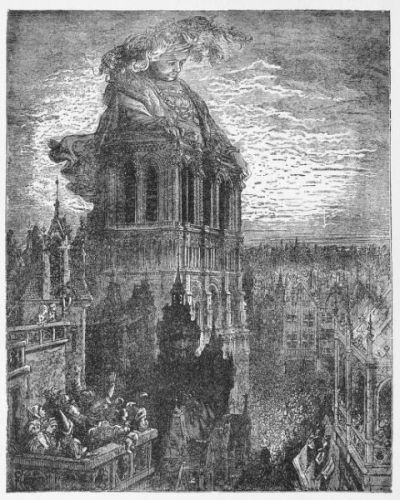

Long before the day whenFielding and Smollett began tobe read on the sly, and beforethe comic Muse of Congreveand Wycherly began to belooked at askance, that Englishmoral sentiment, over which Macaulaywas to philosophize morethan a century later, had solidifiedin ignoring Rabelais. Nothingis to be said against the sentiment itself. This has always beenfairly righteous, if just a bit undiscriminating. A great humorist,showing himself content to grovel in the dirt, is, beyond question,deserving of black looks and shut doors. But more than most oldmasters of a type, strong, albeit coarse, Rabelais—from the distinctlymarked physical attributes of his chief personages—mayclaim certain good points which, drawn out and grouped together,ought to fall within the circle of those tales which interest children.

I have read Rabelais twice in my life. Each time, I have readhim in that old French, which has no master quite so great as he;and each time in Auguste Desrez's edition, which, in its carefulTable des Matières, learned glossary, quaint notes, Gallicized Latinand Greek words, and a complete Rabelaisiana, shows the devotionof the rare editor, who does not distort, because he understands,the Master whom he edits. When I first peeped into his pagesI was a lad, altogether too young to be tainted by profanity,while I skipped, true boy-fashion, whole pages to pick out thewondrous story of his Giants. When I came back to him, aftermany years, I was both older and, I hope, wiser. Being older,I had learned to gauge him better, both in his strength and in hisweakness. I had come to see wherein an old prejudice was toojust to be safely resisted; and, on the other hand, wherein it hadgot to be so deeply set that it had hardened to injustice. As I wenton, it did not take me long to discover that it was quite possible formy purpose—following, indeed, the path unconsciously taken in myboyhood—to divide Rabelais sharply into incident and philosophy.That this had not been thought of before surprised, but did not dauntme. I said to myself: I shall limit the incident strictly to his threeGiants; I shall