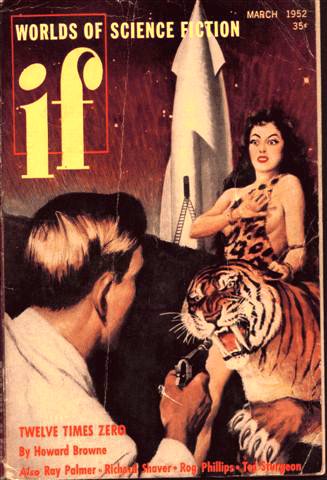

Of Stegner's Folly

By Richard S. Shaver

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from If Worlds of ScienceFiction March 1952. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence thatthe U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

When a twenty-foot goddess walked out of the jungle, theyknew Stegner wasn't kidding.

Old Prof Stegner never foresaw the complications his selectiveanti-gravitational field would cause. Knowing the grand old man as Idid, I can say that he never intended his "blessing" should become thecurse to mankind that it did. And the catastrophe it brought about wascertainly beyond range of all prophecy.

Of course, anyone who lived in 1972 and tried to get inside Stegner'sweird life-circle must agree that you can get too much of a good thing.Even a pumpkin can get too big—and that's what happened when the Profturned on his field—things got big; and too darned healthy!

I was there the day Stegner announced the results of ten year's researchon his selector. Nearly everyone present had read the sensationalarticles concerning his work in the feature sections of the big townnewspapers. Like the rest, I had a vague idea of what it was about. Itseemed the Prof had developed a device that repelled various particlesof matter without effecting others. In short, if he turned on hisgadget, gravity reversed itself for certain elements, and they went awayin a hurry. Like this: he could take oxide of iron, turn on hisselective repellor, and the rust rather magically turned to pure ironwithout the oxygen. Or, he could take a pile of mixed chemicals, turnhis control knobs to the elements known to be present in the mixture,and presto! Only certain ones, of his choosing remained. The atoms ofthe other elements conveniently left the vicinity.

All of which was interesting and extremely useful. The Prof promptly gotrich selling patent rights to the device, tuned to certain frequencieswhich refined heretofore unrefinable ores. His device made animprovement over most known methods of refining, costing far less inoperation than the standard and often complicated methods previously inuse.

Money gave the old man his opportunity. He fitted out a big research labin California, not too far from civilization, but secluded enough forsecrecy. Then he set about to try his selective repellor on livingtissues. His suspicion, that wonderful things could be discovered if hetuned his anti-gravitational field to the undesirable elements in thebody, was confirmed. Like lead poisoning—something no doctor can cureif it is severe. He found that he could cure a case of lead poisoningmerely by making the lead go away from there via the field. Morewonderful things began to come out of the Stegner laboratory, and hemade a lot more money.

Which was all very well indeed, only the Prof couldn't leave well enoughalone—he had to delve and pry. He had his own theories about diseaseand its cause, old age, and so on—all nuttier than a fruit cake. He wassomething of a crank on various health foods and diets that left outfoods raised with chemical fertilizers. He had an organic garden, agarden where no chemical fertilizer or poison spray was ever used. Andafter all, who knew better than the Prof—who could isolate them in atrice—how many poisons could be found accumulating in the average humanbody, consumed along with perfectly harmless foods during a lifetime?

Anyway, when the Prof called in the press, myself among them, he wasreally excited. "Gentlemen," he said, "I have solved the greatestmedical puzzle of all time. Before me, no med