George Manville Fenn

"Off to the Wilds"

Chapter One.

Coffee and Chicory, but not for Breakfast.

“Just look at him, Dick. Be quiet; don’t speak.”

“Oh, the dirty sunburnt little varmint! I’d like the job o’ washing him.”

“If you say another word, Dinny, I’ll give you a crack with your own stick.”

“An’ is it meself would belave you’d hurt your own man Dinny wid a shtick, Masther Jack? Why ye wouldn’t knock a fly off me.”

“Then be quiet. I want to see what he’s going to do.”

“Shure an’ it’s one of the masther’s owld boots I threw away wid me own hands this morning, because it hadn’t a bit more wear in it. An’ look at the dirty unclane monkey now.”

“He’ll hear you directly, Dinny, and I want to see what he’s going to do. Hold your tongue.”

“Shure an’ ye ask me so politely, Masther Jack, that it’s obliged to be silent I am.”

“Pa was quite right when he said you had got too long a tongue.”

“Who said so, Masther Jack?”

“Pa—papa!”

“Shure the masther said—and it’s meself heard him—that you was to lave your papa at home in owld England, and that when ye came into these savage parts of the wide world, it was to be father.”

“Well, father, then. Now hold your tongue. Just look at him, Dick.”

“It’s meself won’t spake again for an hour, and not then if they don’t ax me to,” said Dennis Riley, generally known as “Dinny,” and nothing more. And he, too, joined in watching the “unclane little savage,” as he called him, to wit, a handsome, well-grown Zulu lad, whose skin was of a rich brown, and who, like his companion, seemed to be a model of savage health and grace.

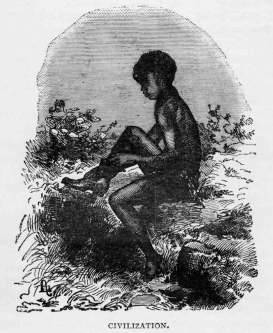

For there were two of these lads, exceedingly lightly clad, in a necklace, and a strip of skin round the loins, one of whom was lying on his chest with his chin resting upon his hands, kicking up his feet, and clapping them together as he watched the other, who was evidently in a high state of delight over an old boot.

This boot he had found thrown out in the fenced-in yard at the back of the cottage, and he was now seated upon a bank trying it on.

First, he drew it on with a most serious aspect, held out his leg and gave it a shake, when, finding the boot too loose, he took it off and filled the toe with sand; but as the sand ran out of a gap between the upper leather and the sole close to the toe and as fast as he put it in, he had to look out for something else, which he found in the shape of some coarse dry grass. With this he half filled the boot, and then, with a good deal of difficulty, managed to wriggle in his toes, after which he drew the boot above his ankle, rose up with a smile of gratified pride upon his countenance, and began to strut up and down before his companion.

There was something very laughable in the scene, for it did not seem to occur to the Zulu boy that he required anything else to add to his costume. He had on one English boot, the  same as the white men wore, and that seemed to him sufficient, as he stuck his arms akimbo, then folded them as he walked with head erect, and ended by standing on one leg and holding out the booted foot before his admiring companion. This was too much for the other boy, whose eyes glittered as he made a snatch at the boot, dragged it off, and was about to leap up and run away; but his victim was too quick, for, lithe and active as a serpent, he dashed upon the would-be robber, and a fierce struggle ensued for the possession of the boot.

same as the white men wore, and that seemed to him sufficient, as he stuck his arms akimbo, then folded them as he walked with head erect, and ended by standing on one leg and holding out the booted foot before his admiring companion. This was too much for the other boy, whose eyes glittered as he made a snatch at the boot, dragged it off, and was about to leap up and run away; but his victim was too quick, for, lithe and active as a serpent, he dashed upon the would-be robber, and a fierce struggle ensued for the possession of the boot.

John Rogers, otherwise Jack, a frank English lad of about sixteen, sprang forward to separate the combatants, but Dinny, his father’s servant, who had been groom and gardener at