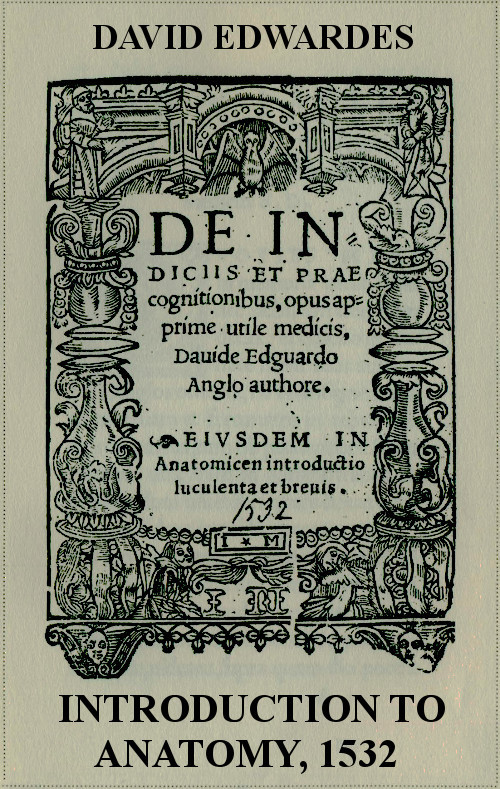

DAVID EDWARDES

Introduction to

Anatomy

1532

A FACSIMILE REPRODUCTION

WITH ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND

AN INTRODUCTORY ESSAY

ON ANATOMICAL STUDIES IN

TUDOR ENGLAND

BY

C. D. O’MALLEY

AND

K. F. RUSSELL

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

1961

English translation and Introduction

© C. D. O’Malley and K. F. Russell, 1961

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, OXFORD

BY VIVIAN RIDLER

PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

TO THE MEMORY OF

CHARLES SINGER

FRIEND AND MENTOR

CONTENTS

Grateful acknowledgements are made forassistance from the National Science Foundation in thepreparation of this work; to the British Museum forpermission to photograph the only copy of DavidEdwardes’s Introduction known to be in existence; andto the Wellcome Trust whose help made the publicationof this work possible.

INTRODUCTION

On 22 August 1485 the battle of Bosworth providedits victor with the throne of England. Richard IIIdied sword in hand and was unceremoniouslyburied in the Grey Friars at Leicester, and on that sameday the victor, Henry Tudor, was as simply crowned andacclaimed by his troops as Henry VII. So began the Tudordynasty in England which was to last until the death ofElizabeth in 1603, to be one of the most colourful periodsof English history and to witness the arrival of the Renaissancein England. Later than its manifestation on theContinent, but thereby reaping the benefits of continentaldevelopments, English humanism as a result was soon tobecome no mean rival. The development of English literatureis too well known for comment, while classical studies,and especially those in Greek, were to rival their continentalcounterpart by the end of the first quarter of the sixteenthcentury. Science, however, and more particularlymedicine, were laggards.

In those closing years of the fifteenth century whichushered in the new Tudor monarchy the art of healingderived from two sources, the universities of Oxford andCambridge and the organizations of barbers and surgeons.At Oxford medical teaching was organized by the fifteenthcentury, and medicine constituted one of the four facultiesof the university together with theology, law, and arts. Yetat Oxford, as at Cambridge, the medical curriculum waslong to remain medieval.[1] Both schools had taken theirmodel from Paris, but whereas Parisian medicine had2begun to stir and advance in the fifteenth century, theEnglish universities remained somnolent. At Cambridgethe degree of Doctor of Medicine required altogethertwelve years of study based upon lectures and discussionsdrawn from medieval sources. While it is true that twoyears of this time were to be spent in the practice of medicine—seeminglya borrowing