THE PURE OBSERVERS

BY B. J. ROGERS

The history of space-flight begins before

man. While our planet still lay wrapped in

its dream of isolation, other intelligences

watched from above—minds pure, undying,

noble—and pathetically vulnerable....

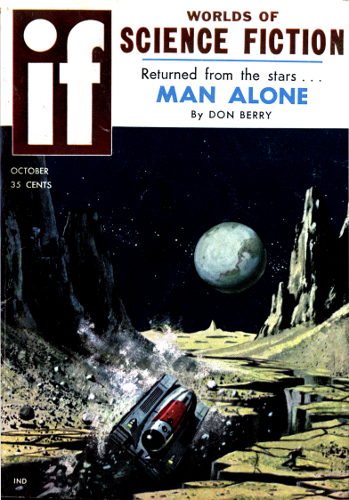

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, October 1958.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"Oh, he is dead!" my mind cried out.

Novna, my dear, I am writing this as a release for my conscience.Those things which trouble me are not such as one exchanges with vigilcompanions, or indeed with anyone not bound by ties like ours.

If I were at home with you I would exchange with your soul in a momentthe feeling of my own, but distance permits no such consolation and itis not suitable for me to exchange so familiarly with my colleagues.

I find myself questioning the value of our customary refusal tocommunicate thoughts of a delicate and sensitive nature. The Earthpeople, who speak their thoughts, perhaps are less primitive thanwe like to imagine. They seem to have no sense of the danger ofoverwhelming the soul of another with unwanted confidences. The purelyvocal nature of their communication does not admit an excessive degreeof emotion to their relationships. They do not have to erect anyartificial barriers between each other, as we must who exchange on amental level.

These doubts of mine never could have arisen if we men of Hainos hadnot presumed to observe the alien ways of those creatures on the thirdEarth, so like ourselves and yet so remote, though we have hoveredabove them, listening and watching, for twelve of their generations.

This vigil, though it is to last but one journey around the sun, hasseemed longer and less fruitful than all the others. I think I shallnot come again, but leave such work to those who can remain efficientand disinterested Observers, unmoved by doubt and anxiety. Novna, youmust begin to think what we two shall do with the rest of our eternity,for now that I have spent some small portion of mine in fifty vigils, Ifind they have become distasteful. We might go to the Palace of Art andstudy to be poet-priests. My last vigil has convinced me that I am morefitted for that life than this.

When our mission left Hainos for the third Earth, there was aboard ourship the poet-priest Gven. You must remember the many nights we satbeneath the rocks by the ocean, listening as his soul gave ours hissongs. Innocent they were, and filled with talk of purity and light,though Gven is as old as the rest of us, even if he is as differentfrom you and me as the Earth child is from its parents.

You have never seen him, I think. He is smaller than I, slight ofbuild and tender-faced. How out of place he looked among the ship'ssturdy men of science, with their ages of discipline and austeritywritten indelibly into their features. They did not want him. They toldthe commissioner that they did not want him.

"Let him stay at home," they said, "and sing his songs to those whowish to listen."

But the commissioner himself, and, I suspect, the commissioner's wife,was as fond as any of Gven and his songs, so he said Gven was to comeif he liked.

Poor Gven tried hard enough to make us like him. He offered us the onlygift he had, that of his songs, but no one cared to hear them exceptme, and I was ashamed to say so. In the end he was reduced to sittingfor hours, looking out into the