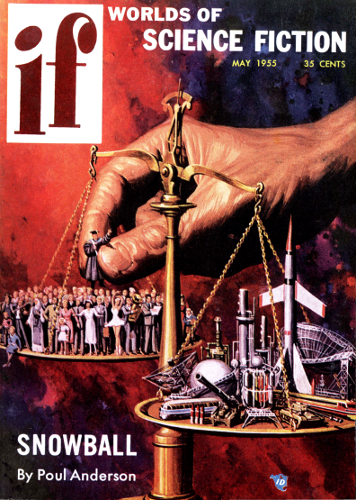

THE PACIFISTS

BY CHARLES E. FRITCH

Parker was a trouble maker wherever they

landed. But here was the planet ideal, a

chance he had awaited a long, long time—easy,

like taking candy from a baby....

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, May 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Like a lone sentinel, the house stood apart at the edge of the village,a white cube with no windows. The door stood open, a dark hole againstthe white brick. The house was silent. The village beyond was silent.

"They must have seen us land," Compton said, a little wildly. "Youcan't set down a rocket ship a hundred yards from somebody and not havethem notice. They must have seen us!"

"Unless no one lives here," Parker amended. "This may be a ghost city."

"He's right," Hinckley agreed. "There might not be anyone living here,or anyplace on the planet for that matter. We've found very little lifein these alien star-systems, and it's varied from primitive to ancient.Perhaps this society became old and died before any of us were born."

The three Earthmen stood at the base of the spaceship, their spacesuitheadpieces thrown back so they could breathe in the cool thin air. Theystood there peering into the deathly stillness.

"I hope there are people living here," Parker said. "It's been morethan a month now—"

"Well," Hinckley said, "let's find out." He waved them forward.

They were fifty feet from the house when a woman appeared in thedoorway with a silver vase. She was dressed in a grey flowing robe thatcovered her from neck to ankles.

"A young woman," Hinckley breathed, staring. "A woman just like any onEarth!"

His voice was loud in the silence, but the woman took no notice. Shestooped and began filling the vase with sand. The two men with Hinckleyshifted anxiously, settling the sand beneath their boots. Behind themthe great spaceship pointed its nose at the sky.

Parker was staring intently at the girl. "I'm going to like thisplace," he said slowly.

They walked forward, crunching sand. But the girl took no notice oftheir approach. She was kneeling beside the house, scooping tinyhandfuls of sand into the silver vase. When they were within five feetof her, Hinckley cleared his throat. She did not look up. He coughed.

"Maybe she's deaf," Parker suggested vaguely. His eyes wanderedappraisingly over her youthful body; he licked dry lips.

Hinckley moved forward and stood before the girl. Her small white handsdug into the sand, scooping around his boots as though not aware ofthem.

"And blind, too?" Compton wanted to know. "And without the sense oftouch?" There was a strange quality to his voice, as though someprimitive part of his unconsciousness was telling him to run.

Hinckley bent to tap the girl lightly upon the shoulder. "Pardon me,Miss. We're visitors from Earth," he told her.

But she paid no attention to the sound of his voice, and he steppedback, puzzled.

"Now what?" Compton wanted to know. He looked around him nervously, atthe house, the speckled sand, the rocket squatting behind them. "I hopeall the natives aren't like this."

"I do," Parker said, licking his lips thoughtfully and keeping his gazeon the girl. "I'd just as soon have them all like this. It might beinteresting."

Compton flushed. "What I meant—"

"He knows what you meant," Hinckley said harshly. "And there won'tbe an