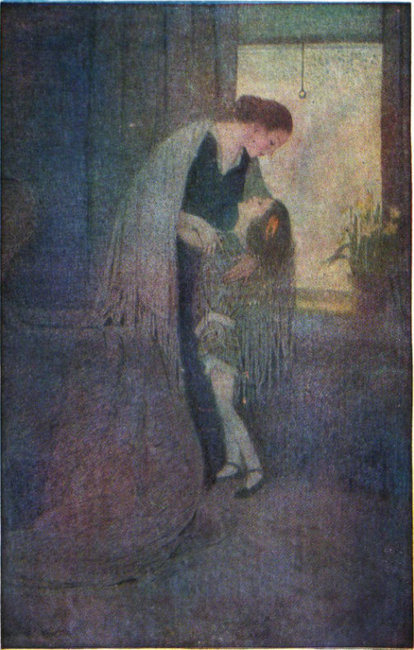

“I saw her lift her little arms, and I saw the mother stoop and gather her to her bosom”

THE SHADOWY THIRD AND OTHER STORIES

THE SHADOWY THIRD

When the call came I remember that I turned from the telephone in aromantic flutter. Though I had spoken only once to the great surgeon, RolandMaradick, I felt on that December afternoon that to speak to him only once—towatch him in the operating-room for a single hour—was an adventure whichdrained the colour and the excitement from the rest of life. After all theseyears of work on typhoid and pneumonia cases, I can still feel the delicioustremor of my young pulses; I can still see the winter sunshine slantingthrough the hospital windows over the white uniforms of the nurses.

“He didn’t mention me by name. Can there be a mistake?” I stood,incredulous yet ecstatic, before the superintendent of the hospital.

“No, there isn’t a mistake. I was talking to him before you came down.”Miss Hemphill’s strong face softened while she looked at me. She was a big,resolute woman, a distant Canadian relative of my mother’s, and the kind ofnurse I had discovered in the month since I had come up from Richmond, thatNorthern hospital boards, if not Northern patients, appear instinctively toselect. From the first, in spite of her hardness, she had taken a liking—Ihesitate to use the word “fancy” for a preference so impersonal—to herVirginia cousin. After all, it isn’t every Southern nurse, just out oftraining, who can boast a kinswoman in the superintendent of a New Yorkhospital.

“And he made you understand posi