TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Inconsistencies in hyphenation have not been corrected, punctuation has been silently corrected. A list of corrections to the text can be found at the endof the document.

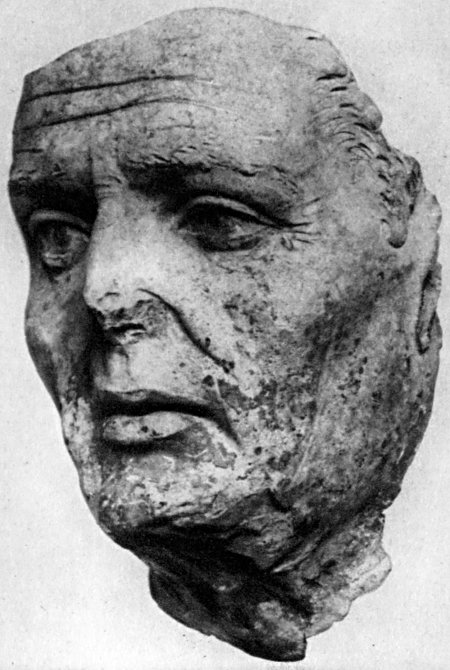

M. TULLIUS CICERO.

M. TULLIUS CICERO.FROM THE JAMES LOEB COLLECTION.

CICERO

DE OFFICIIS

WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY

WALTER MILLER

LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO.

MCMXIII

INTRODUCTION

In the de Officiis we have, save for the latterPhilippics, the great orator's last contribution toliterature. The last, sad, troubled years of his busylife could not be given to his profession; and heturned his never-resting thoughts to the second loveof his student days and made Greek philosophy apossibility for Roman readers. The senate had beenabolished; the courts had been closed. His occupationwas gone; but Cicero could not surrender himselfto idleness. In those days of distraction (46-43 b.c.)he produced for publication almost as much as in allhis years of active life.

The liberators had been able to remove the tyrant,but they could not restore the republic. Cicero'sown life was in danger from the fury of mad Antonyand he left Rome about the end of March, 44 b.c.He dared not even stop permanently in any one ofhis various country estates, but, wretched, wanderedfrom one of his villas to another nearly all the summerand autumn through. He would not sufferhimself to become a prey to his overwhelming sorrowat the death of the republic and the final crushingof the hopes that had risen with Caesar's downfall,but worked at the highest tension on his philosophicalstudies.

The Romans were not philosophical. In 161 b.c.the senate passed a decree excluding all philosophersand teachers of rhetoric from the city. They had notaste for philosophical speculation, in which theGreeks were the world's masters. They were intensely,narrowly practical. And Cicero was thoroughly[x]Roman. As a student in a Greek university he